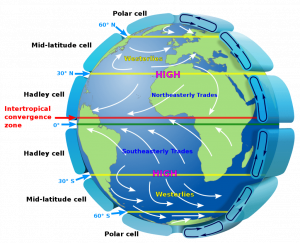

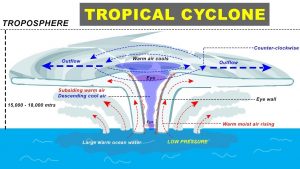

Tropical cyclones form over warm ocean waters where temperatures are around 26º C or higher, gaining energy from the heat and moisture of the sea. Once they develop, their movement is largely determined by surrounding winds, similar to how a leaf drifts along a flowing river. Cyclones generally form in tropical regions between 5º and 20º north and south of the equator. In these areas, trade winds blow from east to west as part of the global Hadley circulation. Warm air rises near the equator, moves toward higher latitudes, cools and sinks around 30º latitude, then flows back toward the equator. The rotation of the Earth deflects this returning air westward, creating the easterly trade winds.

Cyclones generally form in tropical regions between 5º and 20º north and south of the equator. In these areas, trade winds blow from east to west as part of the global Hadley circulation. Warm air rises near the equator, moves toward higher latitudes, cools and sinks around 30º latitude, then flows back toward the equator. The rotation of the Earth deflects this returning air westward, creating the easterly trade winds.

These winds tend to push storms westward, which explains why cyclones in the Bay of Bengal move toward India’s east coast, Atlantic storms travel from Africa to the Caribbean and the Americas, and Pacific storms often head toward Asia and Australia.

While cyclones gain strength from warm ocean waters offshore, the prevailing winds control their path. They may also interact with other atmospheric systems, such as mid-latitude westerlies, which can alter their direction. Sometimes this steers storms into open waters, but often they continue toward land.

While cyclones gain strength from warm ocean waters offshore, the prevailing winds control their path. They may also interact with other atmospheric systems, such as mid-latitude westerlies, which can alter their direction. Sometimes this steers storms into open waters, but often they continue toward land.

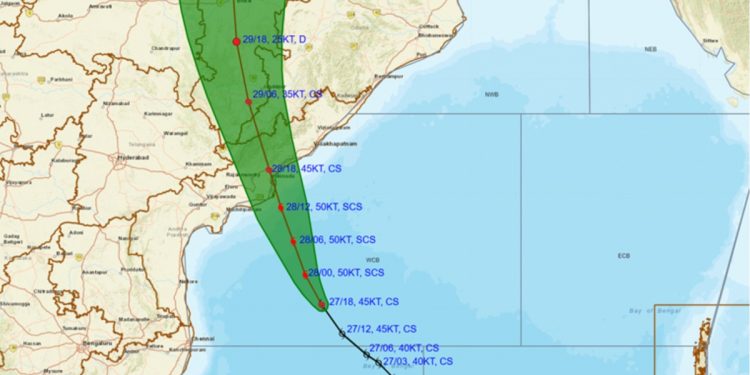

For example, in December 2023, Cyclone Michaung lingered offshore for several hours before making landfall because the steering winds over the Bay of Bengal were weak.

In theory, if global wind patterns were reversed, cyclones would rarely make landfall and would drift over open water. The Arabian Sea presents an interesting case. Cyclones there could be expected to move toward the Arabian Peninsula or Africa, but they often move toward India because of monsoon winds. During the southwest monsoon from June to September, surface winds blow from the southwest toward the northeast, steering storms toward India. This explains why cyclones in the Arabian Sea frequently hit western India, including Gujarat, Maharashtra, and sometimes Kerala

The Arabian Sea presents an interesting case. Cyclones there could be expected to move toward the Arabian Peninsula or Africa, but they often move toward India because of monsoon winds. During the southwest monsoon from June to September, surface winds blow from the southwest toward the northeast, steering storms toward India. This explains why cyclones in the Arabian Sea frequently hit western India, including Gujarat, Maharashtra, and sometimes Kerala

Outside the monsoon season, the northeast monsoon brings dry air from the Indian subcontinent toward the equator and Africa, which can push cyclones westward. However, formation is less likely in winter and early spring due to cooler waters and stronger wind shear.

Discussion about this post